Can ChatGPT Replace Your Lawyer? These Cases Show What’s Possible

Artificial intelligence is stepping into the courtroom, and not as a silent observer. Across the U.S., individuals once unable to afford legal counsel are now relying on AI tools like ChatGPT and Perplexity to represent themselves—and surprisingly, many are succeeding.

From eviction battles in California to debt disputes in New Mexico, these tools are reshaping how ordinary people handle legal challenges.

A New Legal Ally

Lynn White, a Long Beach resident, faced eviction from her trailer park after falling behind on rent. Despite losing her initial case with a lawyer’s help, she decided to appeal using ChatGPT and the AI-powered search tool Perplexity. White used the chatbot to analyze court documents, identify procedural mistakes, research laws, and draft filings. The result? Her eviction notice was overturned, saving her from roughly $55,000 in penalties and $18,000 in overdue rent.

“It was like having God up there responding to my questions,” White said. After months of effort, she credited AI for her victory. Initially using ChatGPT’s free version, she later upgraded to its premium plan and subscribed to Perplexity Pro—each costing $20 per month.

White isn’t an isolated case. A growing number of Americans are skipping traditional legal representation, turning instead to generative AI for research, drafting, and courtroom strategy.

The Rise of AI-Driven Self-Representation

Instagram | public_counsel | NBC’s findings show AI is a crucial tool for pro se litigants to navigate complex law.

NBC News interviewed over 15 individuals representing themselves—known as pro se litigants—along with lawyers, nonprofit leaders, and AI startup executives. The findings were clear: while AI sometimes misleads users with inaccurate information, many find it an indispensable tool for navigating complex legal systems.

“I’ve seen more pro se litigants this past year than I have in my entire career,” said Meagan Holmes, a paralegal at Thorpe Shwer in Phoenix.

Still, legal experts caution against relying solely on AI. Many chatbots lack safeguards for professional use. Google’s policy explicitly warns users not to depend on its services for legal or financial advice. Yet most AI systems, including ChatGPT, readily respond to legal queries—with disclaimers tucked away in fine print.

Perplexity’s spokesperson, Jesse Dwyer, acknowledged the risks but emphasized accuracy remains their top focus: “We don’t claim to be 100% accurate, but we work on it relentlessly.”

Real Cases, Real Results

Staci Dennett, a home fitness business owner in New Mexico, used ChatGPT to settle an unpaid debt lawsuit. She asked the chatbot to critique her legal arguments “like a Harvard Law professor,” refining them until she reached what she called an “A-plus” version. Her final settlement saved her over $2,000, and even opposing lawyers commended her grasp of the law.

These stories show how AI can serve as a “virtual law clerk,” offering everyday people access to resources once reserved for professionals.

When AI Gets It Wrong

However, AI’s limitations can have serious consequences. Generative models are prone to “hallucinations”—fabricated facts or court cases presented as real. Holmes noted that many AI-written legal documents cite nonexistent cases, forcing courts to dismiss them.

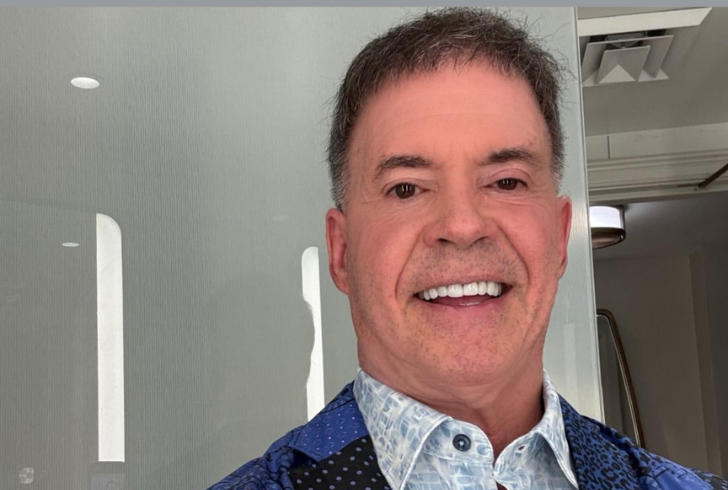

Jack Owoc, the founder of Bang Energy, learned this the hard way. Representing himself after losing a $311 million false advertising case, he filed motions containing 11 fake citations produced by AI. The court sanctioned him and required disclosure of AI use in future filings.

Instagram | jackowoc.ai | Bang Energy’s founder, Jack Owoc, used 11 fake AI-generated citations and was sanctioned by the court.

Earl Takefman, involved in several Florida business disputes, faced similar trouble when ChatGPT fabricated a case called Hernandez v. Gilbert (1995)—twice. “I told it that it really messed me over,” he said, “and it apologized.” Though the judge spared him from sanctions, the incident taught him to double-check every reference manually.

Legal researcher Damien Charlotin has tracked more than 280 U.S. cases where courts discovered AI-generated errors. These range from nonexistent citations to misrepresented case law, with fabricated details proving especially common among self-represented litigants.

The Debate Over Responsibility

Some legal experts argue that using AI doesn’t excuse errors. Robert Freund, an attorney in Los Angeles, said: “What I can’t understand is an attorney betraying the most fundamental responsibilities to clients and filing arguments based on total fabrication.” He added that false citations waste valuable court resources and undermine credibility.

In one recent California case, a lawyer was fined $10,000 for submitting 21 hallucinated quotes—a record penalty so far.

Balancing Accessibility and Accuracy

Not all AI users are reckless. Matthew Garces, a nurse from New Mexico managing nearly 30 federal lawsuits, credits AI tools for giving him “access to courthouse doors that money often keeps closed.”

Despite being reprimanded by judges for inaccurate filings, Garces continues to refine his approach, seeing AI as essential for organization and legal drafting.

Teaching AI Literacy in Law

Instagram | public_counsel | Zoe Dolan’s class taught unrepresented litigants to use AI responsibly for documents and citations.

Some legal aid organizations are embracing this shift constructively. Zoe Dolan, supervising attorney at Public Counsel in Los Angeles, launched a class teaching pro se litigants how to use AI effectively—fact-checking responses, structuring documents, and verifying citations. Participants, including White, later reported courtroom wins.

“This is the most exciting time to be a lawyer,” Dolan said. “The impact one advocate can now have is only limited by imagination and structure.”

The Future of AI in Legal Practice

Attorneys like Andrew Montez of Southern California view AI as a valuable supplement, not a replacement. Montez uses AI for brainstorming and research but never inputs real client information. “Going forward, every attorney will have to use AI in some way,” he said. “Otherwise, they’ll be outgunned.”

Still, Montez warns that AI lacks the contextual understanding needed for complex cases. For simpler disputes, like small claims or debt resolution, he believes self-representation with AI could become more common—and more successful.

Lynn White summarized the broader sentiment best: “AI gave me research support, drafting help, and organizational skills I could not access otherwise. It felt like David versus Goliath—except my slingshot was AI.”

While AI tools aren’t perfect, their growing role in the courtroom signals a fundamental shift. As technology evolves, the line between lawyer and litigant is blurring, and access to justice may finally extend beyond those who can afford it.